10 skillful fakes that museums took for originals

Artistic fakes are a very real threat that museums constantly have to contend with. Fake artifacts appear in many museums from time to time, which can be displayed for several years before specialists realize that this is a fake. For counterfeiters, the high price tags attached to these fakes are often an incentive to continue to create fakes. Art fraudsters often go to great lengths to trick museums into acquiring their work. Some fakes are so good that it is difficult for historians and archaeologists to distinguish them from real things. Among the museums that became victims of fakes is even the famous Louvre Museum, where for many years successful copies were exhibited instead of the originals, and no one even knew about it.

Artistic fakes are a very real threat that museums constantly have to contend with. Fake artifacts appear in many museums from time to time, which can be displayed for several years before specialists realize that this is a fake. For counterfeiters, the high price tags attached to these fakes are often an incentive to continue to create fakes. Art fraudsters often go to great lengths to trick museums into acquiring their work. Some fakes are so good that it is difficult for historians and archaeologists to distinguish them from real things. Among the museums that became victims of fakes is even the famous Louvre Museum, where for many years successful copies were exhibited instead of the originals, and no one even knew about it.

1. Three Etruscan warriors

In 1933, the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art added three new works of art to its exhibition. These were sculptures of three warriors of ancient Etruscan civilization. The seller, an art dealer named Pietro Stettiner, claimed that the sculptures were made in the fifth century BC. Italian archaeologists were the first to express concern that statues could be fakes. However, the curators of the museum refused to heed the warning because they believed that they managed to get works of art at a bargain price and did not want to lose them. Later, other archaeologists noted that the statues had unusual shapes and sizes for works of art created at that time.

Parts of the body were also sculpted in unequal proportions, and the entire collection had almost no damage. The museum found out the truth only in 1960, when archaeologist Joseph Noble recreated the statues using the same techniques as the Etruscans, and stated that the statues in the Metropolitan Museum of Art could not be made by the Etruscans. Investigations revealed that Stettiner was part of a large group of fabricators who conspired to create statues and sell them. The team copied the sculptures from the collections stored in several museums, including the Metropolitan itself. One of the warriors was copied from the image of a Greek statue in a book from the Berlin Museum. The head of another warrior was copied from a drawing on a real Etruscan vase, which was exhibited in the museum.

The sculptures also had disproportionate parts of the body, because they were too large for the studio, and this forced the forgers to reduce the size of some parts. One of the sculptures also did not have a hand, because the forgers could not choose in which gesture to represent the hand.

2. Persian mummy

In 2000, Pakistan, Iran and Afghanistan were almost embroiled in diplomatic scandal due to the mummy and coffin of an unidentified 2,600-year-old princess. The remains, commonly called the “Persian mummy,” were discovered when Pakistani police officers raided a house in Haran after receiving a tip that the owner was illegally trying to sell antiques. The owner was a certain Sardar Vali Ricky, who was trying to sell the mummy to an unknown buyer for £ 35 million.

Ricky claimed that he found the mummy and the coffin after the earthquake. Soon, Iran declared ownership of the mummy, believing that the village of Riki was located right on its border. The Taliban, who ruled Afghanistan at that time, later joined the “battle for the mummy.” The mummy was sent to the National Museum of Pakistan and put on public display. Already there, archaeologists have discovered that some parts of the coffin look suspiciously too modern.

In addition, there was no evidence that any tribes in Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan had ever mummified their dead. Further analysis showed that in fact the mummy is the remains of a 21-year-old woman who could well have been a victim of murder. She was sent to the morgue, and police arrested Ricky and his family.

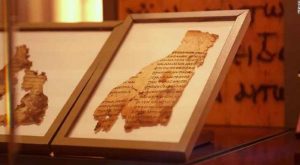

3. Fragments of the Dead Sea Scrolls

Dead Sea Scrolls is a collection of handwritten scrolls containing Jewish religious texts. They were created about 2000 years ago and are among the oldest written records of Jewish biblical passages. Most of the scrolls and fragments are stored in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, and some are in the hands of private collectors and museums, including the Bible Museum in Washington (five fragments). However, in 2018, it turned out that fakes were stored in Washington. Deception was discovered after fragments were sent to Germany for analysis after experts raised the alarm. It turned out that the museum spent millions of dollars on the purchase of fake fragments of the scroll.